I Vinti

I vinti (English: The Vanquished) is a 1953 Italian black-and-white drama film composed of three episodes. The film was dubbed into Italian, the three episodes, although the Paris episode is spoken in French, and the London episode in English.

Regia: Michelangelo Antonioni

Sceneggiatura Michelangelo Antonioni, Diego Fabbri, Suso Cecchi D’Amico, Turi Vasile, Giorgio Bassani, Roger Nimier

Con Franco Interlenghi, Patrick Barr, Eduardo Ciannelli, Anna Maria Ferrero, Peter Reynolds, Etchika Choureau, Fay Compton, Jean-Pierre Mocky.

Drammatico, b/n durata 110′ min. – Italia 1952 Produzione:Film Costellazione – Minerva Video

Tre episodi: in Francia giovani studenti compiono un delitto gratuito; in Italia un ragazzo ricco e annoiato si unisce a un gruppo di contrabbandieri e rimane vittima di una retata; in Inghilterra un giovane paranoico commette un delitto perfetto perché senza movente. Antonioni tocca con concretezza il problema della gioventù deviante nei cui crimini si coagulano moventi oscuri e assurdi, peculiari di un clima sociale, ben resi soprattutto nella fusione di humour nero e sotterraneo sadismo dell’episodio inglese. Tartassato dalla censura.

October 9, 2013 Michelangelo Antonioni’s “I Vinti”

Posted by Richard Brody

In September, 1952, a man identified only as Monsieur I. brought suit to demand that the French government seize a film then in production. The movie was called “Sans Amour” (“Without Love”), comprising three parts, all based on true stories, one of which was the notorious “affair of the J-3 of Melun,” a 1948 case in which a sixteen-year-old boy shot a classmate to death, ostensibly over a girl. Monsieur I. was the father of the girl, Nicole I. She had been convicted of complicity in the crime, but, because she was a minor, neither her name nor her “identity or personality” could legally be published. Monsieur I. accused the filmmaker, Michelangelo Antonioni, and his assistant director, Alain Cuny, of filming a story in which the girl would be identifiable.

The episode was shot and the three-part film was completed under the title “I Vinti” (“The Vanquished”). But Monsieur I. needn’t have worried: the French government soon took its own stringent measures against the episode. First, the export of the negative to Italy (where Antonioni was based) was banned; then, the export of the negative was permitted, but the episode itself was banned within France, because—as the critic Jean de Baroncelli wrote in Le Monde in 1963—“The Ministry of Justice opposes the realization of any screenplay that evokes a judicial affair that implicates people who are still living.” At the time, a decade after the movie’s completion, the ban was still in place.

“I Vinti” is available on DVD in the United States, and will be screened in a new restoration at MOMA in the upcoming series “To Save and Project” (which I write about in the magazine this week). The movie is, in some ways, Antonioni’s most forward-looking early work in its anticipation of his greatest films, from the nineteen-sixties. The substance and style of “I Vinti,” however, were greatly affected by censorship—and the ricochets of that censorship, in turn, were of great moment.

In the mid-fifties, a Parisian critic in his early twenties, François Truffaut, was fascinated by a true-crime case from late 1952: a small-time criminal, Michel Portail, who was driving a stolen diplomatic car, shot and killed a motorcycle policeman who pulled him over, and became the object of a massive manhunt. He was captured in Paris. Truffaut witnessed the police roundups in the city, and his attention was piqued by a detail involving Portail’s American girlfriend. Truffaut was enthusiastic about turning the story into his first feature film, and worked it out with the help of his friend Jean-Luc Godard, but the censorship of the French episode of “I Vinti” made French producers worry about making another movie based on a recognizably familiar true-crime story. When, several years later, Truffaut got his chance with a producer, he turned his attention to another story, the quasi-autobiographical “The 400 Blows,” and after its successful screening at Cannes, in 1959, he passed the crime story along to Godard, who turned it into “Breathless.”

One of the co-writers of Antonioni’s Paris episode was Roger Nimier, a mercurial young writer who was twenty-six in 1952 and had already published four novels with the prestigious publisher Gallimard (as well as two books of essays). Nimier was a flamboyant character and the talk and the scandal of literary Paris, for his lacerating snark (such as his famous insults of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus), his hedonistic ways, and his brazenly right-wing politics. Nimier befriended the elderly collaborator Charles Maurras (who had repudiated the prewar Third Republic and welcomed the dictatorial grip of Marshal Pétain under German occupation) and his cavalier view of love, life, and politics finds its way into the French episode of “I Vinti,” which is centered on a band of students who dream of easy money, riotous travels, and flighty affairs, who thumb their noses at their hard-working and respectable parents and repudiate personal and social responsibility. In one bit of sharp banter that takes aim at holy French myth, one girl explains to a child why Joan of Arc was burned at the stake: “Because she got involved in politics.” (Nimier, who also worked with Louis Malle on the script for “Elevator to the Gallows,” died in a car accident in 1962, at the age of thirty-six.)

Nimier and several other cohorts were the subject of one of the most famous modern French literary essays, by Bernard Frank, published in Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes in 1952, that defined a new, flashy, rightist school, the Hussars (borrowing the title of Nimier’s novel “The Blue Hussar”). And when the French New Wave came along—with its overtly apolitical enthusiasm for movies on aesthetic grounds, with its personal connections to rightist authors, and with the riotous living of many of its characters (as, for instance, the Parisian students of Claude Chabrol’s “Les Cousins”)—some saw it as the cinematic counterpart to the Hussars. It wasn’t, for many reasons—the New Wave drew on a much wider range of influences, and its truly revolutionary work and thought had extraordinarily wide and rapid ramifications, including on the interests and enthusiasms of its directors themselves. But the first time that one of the New Wave directors, Godard, took on a political subject head-on, with “Le Petit Soldat,” in 1960, it was simultaneously considered an outrageous rightist provocation and banned by the government of Charles de Gaulle.

Directors are often great critics, but not necessarily of their own work, because their experience of the process of making a film may distort their idea of its merit. That’s the case, for instance, with “I Vinti.” The movie is a compilation of three short films on the same theme—murders committed by young people—and all three dramas are based on actual events in the three countries in which they were shot: France, Italy, and England. In interviews, Antonioni (who died in 2007) expressed his dissatisfaction with the Italian episode—which, in my view, is the best of the three—due in significant measure to the fact that its story wasn’t the one that he wanted to film.

The original story, published in Pierre Leprohon’s 1961 book about Antonioni, involved Arturo, a young, headstrong man who belonged to a group of young neo-Fascists in postwar Italy who were busily planting bombs in Rome. When Arturo came into conflict with the “adult” political party that looked askance at their wild provocations, he committed suicide—and tried to stage it as a killing in order to be seen as a martyr. But Antonioni’s producers refused to let him film it on political grounds, because, he said in 1978, “the Christian Democrats have always been easy on the Fascists.”

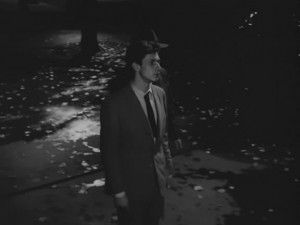

The story that Antonioni filmed in its place involves an utterly apolitical young man—a university student who lives with his parents in a comfortable but stuffy bourgeois household—who takes part in a risky cigarette-smuggling venture and who, when cornered by a customs officer, shoots him and flees. Injured and on the run, the young man makes his way through the rapidly evolving outskirts of town toward the gleaming new building where his girlfriend, who moves in a sleek and wealthy young crowd, is attending a decadent, jazz-juiced party.

There’s no gainsaying Antonioni’s sense that there’s little going on in the story to repay attention to the action—but this may be why the director achieved so much with its filming. The characters play second fiddle to the environment in the Italian episode of “I Vinti”; the actors seem to shrink beside the awesomely looming, coldly oppressive images of modern buildings going up quickly in grandiose modern urbanistic projects. Looking down upon the city through a huge window high up in the revellers’ glossy glass-and-metal apartment building, filming the alluringly pure yet chilling shapes of modern streetlights on a bare new highway, Antonioni foreshadows his great films of the sixties—and the French and English episodes of “I Vinti,” with their more pointedly worked-out stories, hardly do so. The constraints that circumstances placed on Antonioni’s story-telling pushed him, perhaps unintentionally and maybe even unawares, into a freer, stranger, more probing and more inventive way with the camera. He said of his early films:

I chose to examine the inner side of my characters instead of their life in society, the effects inside them of what was happening outside. Consequently, while filming, I would follow them as much as I could, without ever letting the camera leave them. This is how the long takes of “Story of a Love Affair” and “The Vanquished” came about.

The long takes of the French sequence, in particular, are striking—but it’s in the Italian episode, in which his characters seemed diminished by, yet inseparable from, their environment, that, by means of his camera, he truly gets inside them.

P.S. For the French episode, he had wanted the young Brigitte Bardot, but the producers, he said, hesitated to sign an unknown (he cast Etchika Choureau instead); for the English one, he wanted a young actress named Audrey Hepburn, who “unfortunately turned out to be on her way to Hollywood.”